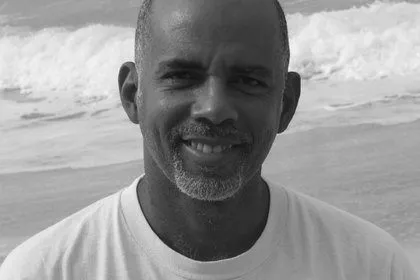

This profile explores how Haitian singer-songwriter and guitarist Beethova Obas turned the disappearance of his father under the Duvalier dictatorship into a lifelong musical journey, rooted in Haiti’s history, spirituality, and daily struggles.

It walks through his childhood, education, landmark albums, collaborations, and artistic philosophy so that readers can understand why his work resonates so deeply with Haitian and international audiences.

Childhood Marked by Haiti’s Political Violence

Beethova Obas was born in Haiti in 1964, into a family where art was central to everyday life. His father, Charles Obas, was a celebrated painter whose canvases often portrayed rainstorms, burdened villagers, and night scenes that many interpret as allegories of life under François Duvalier’s dictatorship.

In 1969, during one of the harshest periods of the regime, Charles Obas went to the National Palace to protest the execution of a cousin. Historical accounts recount that he was taken into custody and never seen again, a fate shared by many dissidents of the era.

For the Obas family, this meant not only emotional devastation but also a drastic loss of social and economic stability.

In later interviews, Beethova has described how his father’s disappearance affected the children’s schooling, their sense of security, and his own perception of life. The absence became a permanent reference point in his identity, influencing both his worldview and his artistic choices.

Among the few physical things Charles left behind were an accordion and a guitar. As a young boy, Beethova was drawn to both instruments. He first experimented with the accordion, then shifted to the guitar, finding it more practical to handle and more suited to the intimate, reflective style of music he would eventually make his own.

Education, Early Compositions, and the Craft of Songwriting

Unlike many singers who begin by performing publicly, Beethova’s path was initially that of a writer and composer. He spent years listening carefully to other musicians, analyzing structures, and teaching himself harmony and melody on guitar and accordion.

Later on, he pursued formal training in both music and economics at a university in the Americas. He has spoken fondly of the voice and music classes he took during this period, describing them as “precious” because they helped refine the self-taught foundation he had already built.

One of his earliest known songs is “Plezi Mizè” (“Pleasure in Misery”), a title that already hints at the tension between joy and hardship that runs through his work. When asked how he learned to write songs, he often emphasizes two habits: listening closely to other composers and practicing relentlessly.

For him, a good songwriter must be an excellent observer and must constantly enrich their musical vocabulary.

Breakthrough with Le Chant de la Liberté

Beethova’s first album, Le Chant de la Liberté (“The Song of Freedom”), was released in 1990 and is frequently described as a turning point in his career. The project carried deep personal symbolism for the family.

According to accounts shared by the Obas brothers, the album was financed in part through the sale of one of Charles Obas’s paintings. Three of the brothers agreed to this plan, seeing it as a way of using their father’s visual art to launch the next generation’s musical voice.

In this sense, the album is both a professional debut and an intergenerational tribute.

The record features eight songs, most of them original compositions by Beethova. One of the tracks, “Koka Bò Kou,” came from composer Pascal Jean Winer. With guidance from respected producer and music journalist Ralph Boncy, Beethova and his brothers selected the strongest material from a larger pool of songs to create a coherent, impactful debut.

Songs such as “Lage’l” (“Let It Go”) and “Kole Zepòl” (“Stick Together”) helped draw attention to the album in Haiti and among Haitian communities abroad. Their blend of poetic lyrics, subtle social commentary, and melodic richness positioned Beethova as a distinctive new voice in contemporary Haitian music.

Haiti as Central Muse and the Album Si

Throughout his career, Haiti has remained Beethova’s primary source of inspiration. When he speaks about the song “Lage’l,” he explains that Haiti itself has been his starting point since the beginning of his career, and that music is simply the artistic language he uses to express what he observes.

In 1994, he released his second album, Si (“If”). Many listeners see this record as a kind of anthology of his work up to that time, gathering themes of uncertainty, hope, and quiet resilience. The title reflects Haiti’s conditional, questioning mood during the early 1990s, when the country was emerging from dictatorship yet still facing instability.

The album includes “Nou Pa Moun” (“We Are Not Human” / “Y’all Ain’t Human”), a powerful social critique performed with a band from Martinique. The song reached audiences beyond Haiti through airplay on French radio and television outlets, contributing to Beethova’s growing presence in the francophone music world and leading to a contract with a French record label.

Covers, Genre Fusion, and a Haitian Reimagining of “Couleur Café”

Although best known for his own compositions, Beethova has also demonstrated a distinctive touch with covers. One of his most notable reinterpretations is “Couleur Café,” originally written and recorded by French songwriter Serge Gainsbourg in the 1960s. In interviews, Beethova has joked that he “warmed the coffee” of Gainsbourg’s song, adding Haitian flavor and rhythmic nuance.

This approach illustrates his broader musical identity. His catalogue blends jazz-inflected ballads, Haitian compas rhythms, and influences from world music. Rather than staying inside a single stylistic box, he allows each song’s message to determine its musical shape. This openness to fusion, grounded in careful listening and study, has helped set him apart from more strictly traditional artists.

Spiritual Resonance and One-Word Philosophies

In 2003, Beethova released Kè’m Pozé (“My Heart’s at Peace”), an album he has described as a spiritual message for a specific period in his life. The songs explore inner calm, faith, and acceptance against the backdrop of Haiti’s enduring social and economic tensions.

Several of his albums carry short, concentrated titles that read like philosophical slogans. Futur (“Future”) points toward long-term hope; Pa Prese (“Don’t Rush”) suggests patience and reflection in a country accustomed to crisis. These titles offer clues about the mindset he brings to composition: each record is conceived as a complete statement rather than just a collection of tracks.

Asked what makes a song resonate with listeners, Beethova tends to answer simply: a song must carry the message people are waiting for and speak directly to their hearts. In his view, music earns its value when it articulates feelings and experiences that listeners struggle to express on their own.

Collaborations, Mentors, and Musical Lineage

Beethova’s growth as an artist did not happen in isolation. Over the years he has collaborated with, and learned from, several prominent figures in Caribbean and Haitian music. Among the names he often cites are Ralph Thamar and Joceline Béroard, associated with the Martinican band Malavoi, as well as the legendary Haitian singer-songwriter Manno Charlemagne.

These artists helped him refine his stagecraft, phrasing, and understanding of how to communicate complex social messages through deceptively simple melodies. With Malavoi in particular, he gained exposure to audiences across the Caribbean and in Europe, sharpening his skills in front of international crowds while remaining rooted in Haitian sensibilities.

Family has remained part of his creative circle too. He has discussed developing a joint project with his brother Manno, sometimes referred to as “Mannothove Cocktail,” a concept that playfully combines their names and suggests a mix of their respective musical tastes.

He has also spoken about working on material honoring Jean-Claude Martineau, known as Koralen, one of Haiti’s most respected lyricists and storytellers.

Artistic Legacy, Discography Highlights, and Advice to New Artists

Across more than eight albums, certain works stand out repeatedly in discussions of Beethova’s legacy. Le Chant de la Liberté remains central because it established his sound and publicly linked his music to his father’s memory. Si is often highlighted for capturing his artistic essence at a pivotal moment in both his career and Haiti’s political transition.

At the same time, Beethova is careful not to rank his own records. Once an album is finished, he tends to say that he loves them all equally and that it is up to listeners to decide which ones speak to them most profoundly.

This attitude reflects his broader philosophy: an artist’s responsibility is to make honest work; history and the public will determine its place.

When advising emerging artists, he returns to the habits that shaped his own journey. Observe your surroundings closely, he suggests, especially the ordinary details of daily life. Deepen your musical knowledge day by day, whether through formal study or careful listening. And above all, cultivate a voice that feels true to your lived experience instead of chasing trends.

What Makes This Guide Different

This profile is designed to be more than a short biography. It connects specific songs and albums to Haiti’s political past and to the personal history of the Obas family, giving readers a clearer sense of why certain themes appear again and again in Beethova’s work.

- Context-rich timeline: Links key albums and songs to historical moments in Haiti and in Beethova’s life.

- Focus on artistic philosophy: Highlights his views on observation, practice, and speaking to “people’s hearts,” not just listing discography facts.

- Attention to family legacy: Explains how the loss of his father and the sale of a painting shaped the meaning of his first album.

- Reader-friendly structure: Uses clear sections and FAQs so that fans, students, and researchers can quickly find specific information.

FAQ About Beethova Obas

Who is Beethova Obas?

Beethova Obas is a Haitian singer, guitarist, and songwriter born in 1964. He is known for poetic songs that blend Haitian rhythms, jazz influences, and socially conscious lyrics, often reflecting on Haiti’s history and the emotional legacy of political violence.

What happened to his father, the painter Charles Obas?

Charles Obas was a prominent Haitian painter whose work frequently depicted life under the Duvalier dictatorship. In 1969, he went to the National Palace to protest the execution of a cousin, was taken into custody, and never returned home. His disappearance had lasting emotional and economic consequences for the entire family and deeply influenced Beethova’s artistic outlook.

Which albums should a new listener start with?

Many listeners begin with Le Chant de la Liberté, his 1990 debut that introduced his signature blend of introspective lyrics and gentle rhythms. Others recommend starting with Si for its mature songwriting and themes of hope and uncertainty, or with Kè’m Pozé for its more explicitly spiritual tone.

How does his music reflect Haiti’s political and social realities?

Beethova rarely writes slogans or overtly partisan songs. Instead, he uses stories, metaphors, and emotional portraits to address issues such as injustice, migration, poverty, and resilience. Tracks like “Nou Pa Moun” and “Lage’l” carry strong social messages while remaining musically warm and accessible.

What genres influence his sound?

His music rests on a Haitian foundation, drawing from styles such as compas and troubadour traditions. At the same time, he incorporates elements of jazz, chanson, and broader world music. His interpretation of Serge Gainsbourg’s “Couleur Café,” for example, shows how he can take a French classic and infuse it with Haitian rhythmic and harmonic colors.

What advice does he offer to young musicians?

Beethova often emphasizes three habits: listening deeply to other composers, practicing consistently, and observing life closely. He encourages young artists to expand their musical vocabulary every day and to write from authentic experience rather than copying whatever happens to be fashionable.

Editorial Note

This article is based primarily on a recorded interview with Beethova Obas, supported by publicly available biographical notes, discography listings, and historical summaries of the Duvalier years. Details about Charles Obas draw on published art histories and documented accounts of his disappearance, while album release dates and titles are cross-checked against music databases and streaming catalogues.

As with any profile of a living artist, new projects and collaborations may emerge after publication, and readers are invited to share corrections or updates so that this portrait can remain accurate and useful.

Last Updated on January 15, 2026 by kreyolicious